You are here

Home ›The Fall in the Average Rate of Profit - the Crisis and its Consequences

From Prometeo 1 Series VII, July 2009 - In our last issue we published an article from Prometeo, the theoretical journal of Battaglia Comunista (PCInt) on the cost of the crisis so far for to the working class. Here we present a second article from that issue on the same theme of the economic crisis, this time on the prospective for the capitalist crisis whose underlying cause is not financial speculation but the permanent problem for capitalism of the declining rate of profit.

Capitalist relations of production are based on a fundamental law - the creation of surplus value through the realisation of profit. The unequal relationship between capital and labour goes beyond capital simply making a profit but involves the extortion of the maximum profit possible. In this context the maximisation of profit is only achievable through extended reproduction based on increasing the exploitation of labour power and thereby increasing the rate of surplus value. The process of accumulation, the concentration of the means of production and the centralisation of capital all flow from this as a natural consequence.

In the early period of capitalist development the objective of extorting the maximum profit was achieved by lengthening the working day as far as was humanly possible. Absolute surplus value was the main source for the maximisation of profit. The working day reached 16 hours in Britain and other major industrialised countries. In this type of accumulation the composition of capital did not significantly change, leading not only to an increase in the mass of profits but also in the rate of profit.

But the finite limits of the working day which, even if taken to extremes cannot go beyond 24 a day, forced capitalists - aiming as always to maximise profit - down the road of reducing the necessary labour time through the everincreasing use of relative surplus value.

This allowed capital to further increase the social productivity of labour, the rate of exploitation and the mass of profit.

However, as technologically advanced machinery replaced labour power the organic composition of capital rose, thus setting in motion the conditions for a fall in the rate of profit. The increase in dead capital in relation to living, or constant to variable capital - in other words a greater increase in capital tied up in machinery and raw materials compared with the number of workers involved in production - leads to an increase in the extraction of surplus value and a huge growth in the mass of profits, but also to a reduction in the rate of profit.

If the rate of profit is the relationship between realised surplus value and the mass of total capital employed, the more the number of workers is reduced in relation to constant capital the more the basis for extracting surplus value is reduced. More precisely, the mass of total capital invested per unit of productive labour increases as does the surplus value produced by any individual workers in the process of accumulation.

The mass of profit increases but the rate of profit declines on the basis of the increase in the organic composition of capital. As is well-known, the formula s/C represents the rate of profit where s is the quantity of surplus value extorted.

This is calculated by multiplying the surplus value created by a single worker by the number of labourers employed.

C is the total social capital, i.e. the sum of constant and variable capital. It follows from this that increasing the latter in relation to the former, i.e. reducing the number of labourers in relation to the increase in capital employed, creates the conditions for a fall in the rate. In mathematical terms, if the numerator diminishes in relation to the denominator, the numerical result is lower. The relationship between s and C is the expression of the organic composition of capital whose increase provokes the fall in the rate of profit.

The organic composition of capital is calculated by comparing constant capital with variable and by expressing the figure for their reciprocal relationship in percentages of the total capital. For example, if the quantitative relationship between constant and variable capital was 80/20 the organic composition would be 400%. If we increase the first figure (constant capital) and lower the second (variable capital) to 90/10 the organic composition would rise to 900%.

The more the organic composition rises, the more it brings into play the law of the tendency for the average rate of profit to fall. Apart from short periods, capitalism cannot escape from this law which is immanent to its relations of production.

Its operation is shown in the specifics of its fundamental contradictions, a course which leads to capitalism’s decline as a mode of production and which brings with it a series of devastating economic and social consequences.

The more the rate of profit declines the harder it is for capital to find ways to express its valorisation. The more the process of valorisation slows, the more the rate of increase of socially produced wealth proportionally decreases. This is despite the enormous increase in productivity and in the exploitation of the labour force. Thus it is really the increase in the social productivity of labour, the growth in exploitation the relative surplus value which is at the root of the law. As Marx says in the Third Volume of Capital (at the beginning of Chapter 13):

“The progressive tendency of the general rate of profit to fall is, therefore, just an expression peculiar to the capitalist mode of production of the progressive development of the social productivity of labour. This does not mean to say that the rate of profit may not fall temporarily for other reasons. But proceeding from the nature of the capitalist mode of production, it is thereby proved to be a logical necessity that in its development the general average rate of surplus-value must express itself in a falling general rate of profit.”

As evidence for this we can see that the rate of growth of world production has been progressively declining due to the high organic composition of capital in the economy. In the decade 1970-80 the rate of increase of international productive capacity was 5.51%. In the following decade of 1980-90 it declined to 2.27%.

In the decade 1990-2000 it reached a miserable 1.09%. The subprime crisis then did the rest, imposing a recession on world production which declined substantially below zero. If we consider the growth of world production per capita for the same period the figures are even worse. From 3.76% in the decade 1970-80, it went to 0.69% in the next decade, finishing up at 0.19% in the decade 1990-2000. The decline in the increase in world production isn’t due to the fact that needs have been satisfied better or that demand for goods and services have autonomously contracted. This decline is due to the difficulty of valorising capital which, discouraged by decreasing profit margins, is invested less and less in real production as it responds to the siren call of speculation. In the same period, albeit with differences from one area to another, plant utilisation never went above 76% whilst speculation attracted more and more capital which previously went to productive investment. Just how the two phenomenon are related can be seen in the fact that where the process of maximising profit becomes difficult capital turns to seek extra or super profits for an additional gain. This adds nothing to the quantity of goods and services produced but it allows big capitals to acquire surplus value produced elsewhere. At the same time it favours the birth of huge monopolies in the real productive sector where the monopolistic price can be used to compensate for the losses arising from the fall in the rate of profit. It also promotes huge financial holdings dedicated to speculation which continue until the bubble bursts and reduces their profits and financial gains to zero.

First there was the Enron, Cirio and Parmalat cases, then the financial crisis linked to subprime mortgages exploded and the entire capitalist system entered the most deep and devastating crisis since the 1930s. We have to add, however, that the financial bubble burst in a real economy which was already in deep crisis and this was the cause and the spring which unleashed everything.

General Electric and General Motors are two prime examples. The two biggest corporations in the world have had recourse to financialisation to deal with their profits crisis. In the space of forty years they went from profit rates of 20% to 5%, and of this 5%, 40% was the result of speculative activity. It is exactly the same on the macroeconomic level. Financialisation developed (in close parallel with the profits crisis) and persists even in periods of partial recovery. Between 1950 and 1980 alone 15% of capital was earmarked for speculation. Between 1980 and 2003 the proportion of speculative capital rose to 25% but no further. This shows three things: the first is that the increasing difficulty of capital valorisation on the part of the real economy induces financialisation of the crisis. In other words, the attempt overcome the lack of profit from production with extra profits or financial returns which supplement the rate of profit and which could be, in part, productively re-invested. The second thing it shows is that there are limits to this. Surplus value and its related amount of profit are formed in the process of production whilst mere financial gain, the recourse to the stock market and speculation, is nothing but a mechanism for transferring surplus value that has already been created. The third thing - which is a synthesis of the first two - is that financialisation of the crisis via speculation, the creation of fictitious capital and parasitism, has an objective limit which cannot be overcome without destroying the very fictitious capital which contributed to its creation. Recently, since the end of the 1990s, stock market crises have followed one another at an extraordinary rate.

Following the bursting of the Russian and Asian speculative bubbles, the US Stock Exchange has produced the greatest destruction of fictitious capital in capitalism’s history, even surpassing that of 1929. Between January 2000 and October 2002 the Dow Jones fell from 11722 to 7286 points, amounting to a 38% loss in its share capital. The NASDAQ, or stock market for high tech firms, fell 80%. Over the same period (March 2000 to the third quarter of 2002) the consequence of the two stock market explosions amounted to a net loss of $8,400 billion. The present crisis has done the rest. Not only has it made major US financial institutions go to the wall, it has forced state intervention to avoid a global failure of the whole credit system and the real economy itself. In the final analysis these speculative bubbles are created by the financialisation of the crisis as capital increasingly turns to increasing its financial revenue and searching for extra profit in order to revive continuously declining profit rates and solve the economic crisis. Its inevitable end only poses the same crisis situation again but at a higher and more critical level. It never escapes from the vicious circle which is typical of capitalism in all stages of its existence but which in its period of decay is devastating. The most obvious example is today, where the economic and financial world face an unprecedented crisis which makes the crises of the early 2000s and even that of the 1930s look pale by comparison.

A low rate of profit not only slows the process of valorisation down, it also makes it difficult for new capital to be created. A capital of high organic composition, with its reduced rate of profit, is forced to accumulate more rapidly. The increased velocity of accumulation produces a growing mass of profit but at the same time lowers the rate of profit and the rate of its valorisation. Exactly the same dynamic explains how in periods of accentuated crisis, distinguished by greater intensity of overproduction of capital unable to find adequate profit margins, capital seeks a variety of ways out, such as economic concentration, financial centralisation and speculation. As Marx said when referring to the contradictions inherent in the law at the beginning of Chapter 15 of Capital Volume Three,

“On the other hand, the rate of self-expansion of the total capital, or the rate of profit, being the goad of capitalist production (just as self-expansion of capital is its only purpose), its fall checks the formation of new independent capitals and thus appears as a threat to the development of the capitalist production process. It breeds overproduction, speculation, crises, and surpluscapital alongside surplus-population.”

And the evidence for this can be seen in the increasingly central role of finance capital, the stock exchange, banks, investment funds and financial holdings.

Never in the history of the fall in the average rate of profit has financial capital assumed such a dominant role within capitalist productive relations. And never before has the struggle between major international currencies for supremacy in the money markets, that instrument for re-appropriating capital, been so violent.

Another effect of the profits crisis is sharpened competition for trade, both domestically and internationally. The more the mechanism for accumulation and valorisation of capital lacks oxygen the harsher the competition between capitals. The race for greater labour productivity, intensified exploitation through the increase in relative surplus value, exacerbates the competition between capitals - a competition which is in turn the product of the profits crisis - and produces, as its first consequence, a historic attack on the living and working conditions as well as the wages of the working class.

Chronologically the evidence is stark. If we compare the times of these attacks with the steepest fall in profits it shows that the economic and social dynamic is the restriction of on profit margins. It all started in the mid 1970s when the rate of profit touched its historic low level of less than 53%. The attack took place on several fronts. In terms of direct and indirect wages it has taken the form of containing labour costs and dismantling the welfare state. Over the last few years wage levels have returned to those of the 70s in every major capitalist country. At the same time social security provision has been reduced.

Increasingly the relationship between capital and wage labour is one involving more flexibility and job insecurity to an extent unequalled in recent history. The profits crisis means that, in addition to reducing labour costs, the capitalists also have to ensure that the labour force is only employed when the valorisation of capital demands it and then that workers are automatically laid off when no longer needed. Capital cannot allow itself the luxury of maintaining a workforce which it is not able to exploit at a rate compatible with its own valorisation needs. Neo-liberalism and globalisation are the real offspring of the profits crisis.

Once extolled by leading bourgeois economists for their extraordinary advantages, they are now being discarded as noxious to the healthy development of capitalism in favour of state intervention.

Yet the severe limits to the process of valorisation within the various national capitals has imposed on big capital the need to overcome all possible barriers to the circulation of capital, commodities and the procurement of strategic primary products and labour power at the lowest possible price. The export of finance capital, the delocalisation of production, the intensive exploitation of the workforce at very low cost, these are all the inevitable corollaries of the slow pace of valorisation typical of the advanced capitalist countries with a high organic composition of capital. If all these objectives are realisable on the level of “normal” imperialist competition, fine, otherwise the force factor intervenes to resolve things. War has become the daily means by which imperialism seeks to obtain desperately needed economic and financial advantages. Is there anything new under the capitalist sun here? Certainly not, but in the present phase of capitalism, warmongering, like any other form of imperialist behaviour, is directly proportional to the gravity of the economic crisis. The tendency for the rate of profit to fall doesn’t create new contradictions or unusual forms of behaviour on the world market, but its does make them worse, pushing them to extremes as serious and desperate as the crisis which produced them.

From the fall of the Soviet Empire to today, whilst the Western bourgeoisie have been crowing about its victory and announcing a new period of peace and prosperity, the abyss of international crises and imperialist war has opened up with an intensity and violence not seen in recent years. In all areas - from economic to political factors, both in domestic and international terms, in the relationship between capital and labour and in the resort to arms - the situation has got worse. Thus interbourgeois tensions have multiplied and intensified in an orgy of decadence where increased exploitation of the proletariat, increased poverty in general, are the only constants in a capitalism trying to put together the conditions for its own survival.

The Decline of the Average Rate of Profit in Figures

In bourgeois literature it is difficult to find clear data on the fall in the average rate of profit. The explanation is obvious. No bourgeois economist, however aware and fearful of the law and its disastrous consequences, can openly confess to investigating the relationship between the mass of profit and the total capital employed to obtain it. Not so much because they don’t want to use Marxist economic categories, although they always reject them, but more simply because they ignore the problem when they put the mass of profit at the centre of the issue and not its rate. Even so, on the basis of the known facts, they do issue warnings about declining returns on industrial investment and the lack of valorisation of invested capital. Publicly they pretend that the explanation lies outside the relations of production, as if it were a question merely of the market or the sale of goods or, at most, of a dysfunction in the productive process and thus that a readjustment of these factors would resolve the problem. Even so, when the capitalist managers attempt to deal with the worrying consequences of the fall in the rate of profit they are forced to deal with the cause of the problem and not its economic effects, thus bringing into play a vast series of countermeasures. A marxist analysis is a lot simpler and more effective because it is stripped of any constraints or mystifications; it is based on the dynamic of the real facts centred round the antagonistic and contradictory aspects of capitalism.

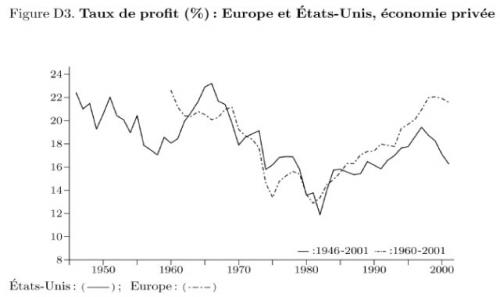

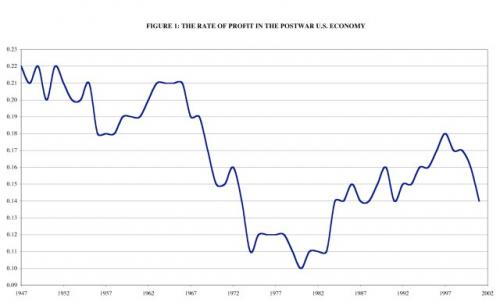

In order to look at both the law of the decline in the rate of profit, and the countertendencies it provokes, we’ll look at the example of the postwar US economy. The choice is forced on us because the figures relating to profit in the US economy are the best known and best researched. According to the French Institute of National Accountability (INSEE) the average rate of profit of the US economy from 1955-2000 declined more than 30% and in the period 2002-5 it fell more than 35%. Further dissection of this statistic reveals that between 1954 and 1979 the rate of profit fell by more than 50%. In the period 1985-97 there was an extraordinary recovery of around 20%, finishing with the years 1997-2002 which saw a fall of 21% from the peak of 1997, a fall which carried on until 2007.

In percentage terms what has happened is that in the first period we went from an average rate of profit of 22-23% to 11-12%. In the second it went back up to 18% only to fall once again in the third to 14%. The figures tell us that, on the basis of changes in the organic composition of capital, the rate of profit has to fall in the long run. In the short term however, due to exceptional circumstances as a result of the operation of certain countertendencies, the rate of profit can grow or else its decline can be clearly slowed down.

See Figure 1 top of p.18: The rate of profit in the post-war US economy

The apparently contradictory aspect derives from the fact that in the first period (the golden age) when the rate went from 22% to 12%, the US economy grew enormously at a rate never reached again in succeeding decades.

The average rate of annual increase in GDP was around 5%, unemployment never rose much above the physiological minimum of around 2% and inflation never went above 2.1%. The US economy dominated world trade. It had an enormous surplus in its balance of payments and was exporting financial capital with a net surplus of 17%. The only explanation for the fall in the rate of profit is the rise in the organic composition of capital, itself driven by the extraction of relative surplus value.

In the space of thirty years the latter increased by 41%, going from 3.58% to 5.03%. These are impressive enough figures in terms of speed and intensity, though they do take place over a long period. The important point is that in the post-war period of economic expansion the need to continually reduce necessary labour time by means of relative surplus value leads to enormously more investment in constant capital than in variable. As dead capital replaces living labour, the source of extraction of surplus value is enormously narrowed, despite an increase in the rate. This explains how the American economy “suddenly” found itself - at the end of the 60s and beginning of the 70s - in its severest economic crisis since 1929- 33. This was when the leading sectors of the economy were overtaken by those of Germany and Japan. Having lost its domination of the world market, the “made in the USA” economy found itself for the first time since the Second World War with a balance of payments deficit on its current account. The USA now had to import capital from abroad as its competitive position declined due to a fall in the rate of profit which had literally halved. The revival of the rate of profit, or rather the slowing of its decline, which took place between 1985 and the end of 1997, was brought about by three factors. The first reason for the recovery is the absolute success of US pressure at the historic Plaza Summit (1985) to the detriment of Germany and Japan. On that occasion the US forced its two major trade and financial rivals to revalue their currencies, thus giving the US economy a competitive edge in commodity prices and therefore on the balance of its current account.

The second was the high interest rate policy promoted by the US Federal Reserve with the aim of recycling the enormous mass of petrodollars which had shifted from the industrialised countries towards the oil producing countries after the first, extraordinary, increases in the price of crude oil.

Taken together, these two actions ensured that the dollar would continue as the main trading currency in all the world markets (92% of all trade was in dollars) and that fresh sources of capital would flow towards the asthmatic US economy to be invested partly at home but mainly abroad. With an increasingly devalued dollar in relation to competing currencies, yet still retaining the dominant international exchange medium, the US was able to recover its competitive advantage thanks to the consequent relative lowering of the price of US goods.

See Figure 2 below: Real Hourly Wages in the USA

The third factor, and certainly the most important, was the reduction in labour costs. Lower taxes on firms, lower money costs and, above all, stagnation of real wages which did not increase at all throughout the entire period. Indeed wages declined thereby contributing to a recovery in the industrial and manufacturing rate of profit to 20%. In the building sector things were even better for the capitalists. Between 1978 and 1993 real wages in this sector have been reduced by 1.1% a year, allowing invested capital to obtain a rate of profit of 50%. We have also to take into account a political factor in regard to this economic data and that is the low level of class struggle which allowed capital to restore profit margins relatively easily. Where working class response to the attacks of a crisis-ridden capitalist system is weak, or even nonexistent, it becomes more practicable for the capitalists to impose the policies of the counter-tendencies with the aim of restoring significant profit margins.

These policies include the infamous calls for sacrifices which are still in force today. Originating in the USA, they have spread to the rest of the Western world with the compliance of the unions and the Left. The export of financial capital and the shift to globalised production did the rest.

Despite the consistent recovery in the rate of profit in the 1980s and 1990s the latest crisis has brought the US economy back to the same precarious situation as at the end of the period of expansion.

By 1998 a series of problems, which the artificial revival of the 1990s had concealed, came to a head. The gambit which had begun with Reaganomics in the 1980s went into crisis. It was based on the draining of world savings to the USA by means of high interest rates and the dominant role of the dollar, but it also involved abandoning some traditional sectors of the economy and a consequent reduction in competitiveness. Moreover, the crisis encompassed foreign investments, the delocalisation of production and the high tech sector on which most of the strategy was based. The increasing indebtedness of the state, of firms, of families trying to buy houses and the means of daily existence, produced a real tragedy whilst the rate of profit inexorably declined. The more profits declined the more the recourse to parasitism, and increased financialisation of the crisis. And so the speculative bubble expanded exponentially, creating the conditions for the explosion in August 2007. The worst aspect of all this is that, once again, the international proletariat is being asked to pay the price. When the speculative bubble - which swelled to provide cheap credit for companies and families as well as the entire economic system - burst, billions of dollars were wiped out in a few days in the fictitious stock market environment. This created a crisis for the whole system of finance, a crisis which revealed the limitations of the entire capitalist system, including a real economy which was already massively weakened, and which was now thrown into the abyss. The housing market collapsed like a house of cards, then all the most important productive sectors, including high tech, began to show signs of collapse. Previous investments in constant capital and software had already reduced productivity. On average, before this further fall in productivity, plants were working at around 60% of capacity. In addition the 3.5% wage rises which were possible during the later stages of the economic boom have become an unsustainable burden on a capitalism in crisis. In a short space of time indebtedness - of the State through the public debt, of businesses which made financialisation their model of development, and of those families who believed in the illusion of easy consumerism - reached new dimensions, throwing the rate of profit of the US economy into the black hole of economic crisis. As a consequence between 2000 and the beginning of 2003 employment fell by 6% and real wages by 1.6%. Productivity fell 40%, plant utilisation 30%, whilst GDP - which had increased by 4.7% in 1997 - fell to 1.3% per annum for the period 2000-3 before going down to minus 6% today.

The overall result is a colossal reduction in net profits. The mass of profit of electronics firms fell from $59.5 billion in 1997 to $12.2 billion in 2002 whilst today the balance sheet has literally folded. In the semi-conductor sector profits fell from $13.3 billion to $2.9 billion. In telecommunications from $24.2 billion in 1996 to $6.8 billion, whilst the service sector saw a drop from $76.2 billion to $33.5 billion.

Finally, in this period the fall in the rate of profit in non-financial activities was on average around 20% with a maximum of 27% compared with the 1997 peak.

All these figures have came to light with the implosion of the subprime crisis.

Returning to the graph (figure 1) and to the breakdown of the period 1945- 2003. We can see the ups and downs of the rate of profit. In the period 1947- 77 there was a decline of 53%. Between 1985-97 there was a recovery of 30% and in the final phase to 2003 it fell 30%.

Subsequently the decline continued until the crash of the last two years.

The result is that over a period of 56 years the American economy has had an average fall in the rate of profit of 30%, with all the economic consequences for capital and the daily existence of the working class. At the international level it has led to increased competition on all the strategically important markets and has produced the tragic phenomenon of war as the only “solution” for the great powers in pursuit of their economic and strategic interests.

See Figure 3 above: Profit Rates for Germany, the USA and Japan

The operation of the law of the fall in the rate of profit in the USA is paralleled, even if the timing is slightly different, in all the major European countries (Britain, France and Germany) and this has opened up a period characterised by six factors.

- An economic attack on the labour force which in terms of length and intensity has no equal in the recent history of international capitalism. The intensified exploitation of labour power through increased productivity brought about by reducing the time and cost of production of commodities has not produced greater wealth or shorter hours for workers, rather it has done the opposite. In a capitalism of high organic composition and low rate of profit an increase in labour productivity implies lower wages, a longer working day, the dismantling of the welfare state and increased job insecurity, as a result of the increased rivalry between capitals pushed into the vortex of competition by the profits crisis.

- The export of financial capital, the dispersal of production, the tireless search for labour markets where the cost of labour power is massively lower than domestic rates, all these have become a condition for the survival of capitalism in crisis. Entire areas have been taken by storm by capitals in search of a higher return from low cost labour markets. Eastern Europe has become one of those areas to which France, Germany and Italy have exported a good part of their manufacturing industry. South East Asia has provided the same function for Japan and lately also for China. The US colossus, though with feet of clay these days, has shifted to Asia and Africa in order to compete with China as well as to those areas of South America which still remain submissive to the imperialist role of Washington.

- Recourse to financialisation through super or extra profits, a systematic recourse to speculation and parasitic activities, the creation of fictitious capital, give a sense not only of the difficulty of valorising capital but even of the decadence of the entire international capitalist system.

- The present crisis has furthermore made it clear that we are not just dealing with a crisis of neo-liberalism but of the entire economic system which has reached the final phase of the third cycle of accumulation. The same bourgeois economists who were only yesterday expressing fears about the role of the State in the economy as the worst of all evils invoke it today as the only road to salvation. They have forgotten that it is not the form of the management of productive relations which can wipe out the system’s contradictions but, on the contrary, it is the crisis of the system which from time to time reveals the limits of whatever type of management is in operation, whether it be liberal, neo-liberal, statist or a mixture of them, depending on the previous historical course pursued by capitalism.

- The need to do everything possible to seek out markets in primary products, above all in oil and natural gas. After the USSR collapsed we witnessed a process of imperialist re-composition which is still going on where entire continents, strategic areas and regions with energy sources have become the flashpoints for confrontations between the great international predators. From Central Asia to Latin America, from the Middle East to Afghanistan, from the Niger Delta to Iraq energy problems with no hope of solution are developing in this imperialist re-alignment. At the same time, of course, there is also a vigorous struggle for hegemony over international currencies. At first, in the first decade of this century, the dollar reigned supreme. Oil was quoted and sold in dollars. Today Russia sells mainly in roubles, Iran and Venezuela also take euros and many Gulf countries are trying to put together a basket of currencies which would generally replace the dollar as the global oil currency. For several years there has been a growing opposition from other currencies to the dollars “droit de seigneur” on the world oil market. Until 1999 92% of international trade took place in dollars. Today it is only 40% with 40% in euros and the remaining 20% in the yen and renminbi.

- The war factor, ever present in imperialism, is taking on a particularly acute character. No market, whether in financial, commercial, foreign exchange or primary products, is free of worrying tensions if not the actual sound of war. Death, destruction, and barbarism are the social and economic constants of the capitalist crisis. The “soft power” of newlyelected president Obama comes as no surprise. Obama will close Guantanamo but how many other prisons of this type will remain in the USA and around the world under the control of the CIA and the US military? He offers his hand to Iran but proposes a renewed sanctions policy if the Tehran regime doesn’t abandon its nuclear policy and prepare to accept oil agreements with USA plc. The US will only leave Iraq if the Baghdad government becomes capable of controlling the military situation and can produce and export oil in the same way as before the war, guaranteeing to the US a privileged partnership in terms of both supply and price. Otherwise American troops will remain in place and at the best estimate this will be a permanent garrison of 40,000 men.

For the Afghan-Pakistan axis things are clearer. The new administration not only has no intention of softening its stance, it has set aside tens of billions of dollars for the so-called war on terror in perfect continuity with the Bush administration. The aim is not to miss the last train to get the energy resources of Central Asia as the US openly competes with Russia and China. At the moment this is only a war of pipelines but it could, if only regionally, change into a real war as in Georgia, North Ossetia and Chechenya, etc. Add to this the renewed effort, as usual following the Bush line in Africa (Chad, Sudan and Nigeria), to combat the deep Chinese penetration, particularly over oil resources. Whatever is happening in these countries in terms of governmental crises, civil wars, clashes between armed groups (each supported by an imperialist interest) is a reproof to the US Government which, despite its changed appearance, is forced to pursue the same old imperialist policy, perhaps less obviously, undoubtedly with a less brutal appearance, but always operating in exactly the same context.

The Temporary Effect of the Counter-tendencies to the Falling Rate of Profit

An analysis of the American economy from the 2nd World War until today reveals two aspects: the first being that over the long term the law of the tendential fall in the rate of profit is continuous. The second is that the extent of the tendency depends on a series of counter-tendencies which, at best, are only effective in the short or medium term. They can momentarily interrupt the fall in the rate or slowdown the velocity of the fall, but since this is an integral part of the process of valorisation of capital itself, they can never reverse the line of march of the law itself.

While capital on the one hand brings into being the conditions for the fall in the average rate of profit, on the other it seeks to contain the consequences by a series of initiatives taken to devalue constant and variable capital.

Thus productivity is increased without affecting, or hardly affecting, the high organic composition of capital which is the basis of the fall in the rate of profit. In normal conditions productivity rises in line with the relative increase in constant capital compared to variable. But more technology signifies more investment in constant capital which replaces a more or less consistent share of the labour force. In other words, the variable capital diminishes more quickly than the rate of increase in constant capital. In this context productivity increases if the cost of the commodities produced is lower than in the previous economic phase, if in the overall total (that is, in the sum of constant and variable capital) there has been a reduction of both. Thus, while there is an increase in productivity, in the rate of exploitation and in the mass of profit, the organic composition of capital also rises and so creates the condition for the fall in the rate of profit. This explains why capital needs to increase productivity with as little as possible increase in the organic composition, in order to slow down or put a brake, in the short run, on the profits crisis. If a particular increase in constant capital allows an increase in the rate of exploitation, with the same number of workers at lower wages, then it is possible to raise the rate of profit. It goes without saying that if such operations remain limited to a single company then there will be very little visible impact on the average rate of profit, but if they are taken up by the big firms in more sectors of production then their impact can be more significant, even if sooner or later, once their mode of reorganising production becomes generalised as a result of local and international competition, the temporary advantages are annulled.

The Devaluation of Variable and Constant Capital

The counter-tendency par excellence concerns the cost of labour and operates by means of its affect on both direct and indirect wages. This is a long-established procedure but in recent times it has intensified enormously as a result of the low profit rates in all the advanced capitalist countries with their typically very high organic composition of capital.

For twenty years the international proletariat has experienced a constant onslaught via the dismantling of the social state - in other words the lowering of indirect and deferred wages, albeit in a variety of ways and at different times.

First in line are key components such as health, pensions and public finance for schools and universities. Reducing unemployment and welfare insurance costs, mainly the state’s contribution but also that of employers; deferring the retirement age, all these have been beneficial for capital. As for businesses, the gradual reduction of sick leave and the elimination of certain conditions from the rubric of official illnesses, count as a saving on indirect wages, again to the advantage of capital. In Italy the employers are trying to get the first three days of illness excluded from workers’ entitlement to sick pay.

One of the most odious practices is the blackmail of immigrant workers and anyone on short term contracts. There is a growing, not-so-veiled practice, of threatening anyone who complains about the flouting of health and safety regulations with the non-renewal of their contract.

As for pensions, the attempt to defer the retirement age has largely succeeded, thus reducing turnover of the workforce and freeing businesses from the need to draw up long term contracts, which would cost too much, and instead to draw up new, short term contracts based on lower wage rates and more flexible working. This is not to mention reduction in breaks and rest periods so that there is no disruption to the rhythm of exploitation. In some cases lunch breaks have been literally halved and time allowed for physiological needs drastically reduced. In metal engineering (vehicles) a favourite practice is the speed-up (more pieces, more halffinished ones, more commodities produced in the same unit of time) without, obviously, a corresponding wage increase. This is an example of the use of relative surplus value which does not alter the organic composition of capital and which, therefore, functions as an effective counter-tendency.

The main way of devaluing variable capital, however, is by a direct attack on wages, on the mass of wages as a whole in relation to the number of workers. Either the overall amount of real wages goes down while the number of workers remains the same, or else the increase in the wage bill is relatively lower than the increase in the number of employees - if ever this actually happens, because usually the opposite occurs - rather, that is, the number of workers diminishes absolutely as a result of the necessity to restructure which, in periods of crisis such as this one, imply redundancies and unemployment.

The precise measures capital adopts to obtain this result are very simple. They all involve drastic cuts in real wages, usually with the help of the unions, in line with the tight margins of the system and the pressure of international competition. The huge plethora of shortterm contracts, of temporary work, of newly drawn-up contracts, all have the common denominator of heightening insecurity for those who do the work. A labour force that is only available during the economic good times when it can be profitably exploited and conversely, which can be got rid of in economic downturns, is an optimum method of containing wage increases and lowering the costs of production. By law every new contract, whatever the specific details, is based on a wage reduction of up to 40% for the same amount of work in the same enterprise. The stubborn vicious circle into which the proletariat has fallen follows scientifically calculated rhythms. Once the old workers who had job security have reached retirement age and the old contracts have come to an end, almost every young worker enters the production process for a determinate (precarious) amount of time and at a lower, much lower, wage than previously. The new way of managing the relation between capital and labour, imposed by the evernarrowing margins of profit realised by enterprises, has the immediate effect of devaluing variable capital without impacting on the increased organic composition of capital. Practices such as this have been in force for two decades, beginning with Japan, the USA and Britain in the 1980s, then, at the beginning of the Nineties, in Europe as well, covering every sector of real production and the main branches of the service sector.

One of the innumerable examples, from the automobile sector, is that of General Motors. Over forty years the biggest car producer in the world went from a rate of profit of 20% to 5% and then to the 1.5% of today, right in the middle of the economic crisis. Despite all the state interventions it has not been able to avoid bankruptcy proceedings. For years it survived on the world market by imposing short-term contracts on its workers, demanding the most extreme mobility inside and outside, with wages up to 40% lower than previously. That most important of American auto companies, the one which has dominated the world market for decades to the point where it was considered a symbol of American and international capitalism, is the paradigm of this crisis.

Throughout the Sixties and Seventies the Detroit company built its productive capacity on a very high organic composition of capital (more investment in constant capital than in variable, more machinery than labour power), thus depressing the profitability of its capital.

Its rate of profit is as can be seen.

This is what persuaded the company directors to withdraw a certain portion of capital from production and switch to speculation with the result, in the short term, of recuperating in the financial sphere what they had lost from real production. So long as the game of creating fictitious capital continued things went well, but as soon as the speculative bubble burst everything collapsed. The stock market losses were added to the losses from production, putting the colossus of American industry on the brink of ruin and possibly further.

Sales have fallen by 56%. GM shares have depreciated enormously. From 46 dollars per share, the value dropped to 3 dollars in December 2008. In February 2009 there was a further depreciation of 23% which brought the share value down to 1.54%, a record historical low for the last 71 years, that is since the Great Depression. The financial arm of General Motors (GMAC) has lost almost the whole of its capitalisation on the Stock exchange. The official reports talk of a deficit of 28 billion dollars which GM is incapable of reimbursing.

GM’s request for refinancing from the State to the tune of 16.5 billion dollars, after already receiving 13.5 billion, opens up a sort of boundless vortex where every white blood cell is devoted to reviving production, or rather to putting the exploitation of labour power (which the crisis has called into question) back on its feet.

But the crisis is not only about statistics.

Behind the figures lie the destinies of millions of workers and their families and the dreadful prospect of being out of work, without unemployment benefit, without a house and facing a future of long term poverty. The first step taken by GM was to immediately shut down five plants in the USA and four in Europe. The same American analysts fear that if GM fails completely, drawing the enormous network of firms dependent on GM into the drama, then a million jobs would be lost. And if the other two majors in the automobile sector, Chrysler and Ford, were to go the same way then almost three million would be unemployed. Over the past year unemployment has risen by seven million, two million of them in the early months of 2009. Overall it’s estimated that unemployment, including the socalled hidden unemployed, has already reached 16 million. The number of workers (in part ex) without medical insurance has gone from 40 to 47 million. This is a social catastrophe which is due to get worse by the end of the year. There hasn’t been a cyclone or any other natural disaster to cause such disturbance, but only capitalism pushed to the edge of ruin by its insoluble contradictions.

It is the same scenario in the rest of the American and international economy, from China to Russia, from Japan to Europe. In Italy the figures are lower only because the epicentre of the crisis is beyond the ocean and because the proportions are different, but even here the causes and mechanisms of the depression are the same. Fiat’s sales have collapsed by 40%, its financial arm has lost all it could lose on the stock market and the value of its shares has fallen to an historic low. Without State intervention (at least 5-6 billion euros) in the form of incentives and cheap credit 600,000 workers, including those in the supply and distribution networks, would have lost their job. It is the same scenario in the rest of the American and international economy, from China to Russia, from Japan to Europe. In Italy the figures are lower only because the epicentre of the crisis is beyond the ocean and because the proportions are different, but even here the causes and mechanisms of the depression are the same. Fiat’s sales have collapsed by 40%, its financial arm has lost all it could lose on the stock market and the value of its shares has fallen to an historic low.

Without state intervention (at least 5-6 billion euros) in the form of incentives and cheap credit 600,000 workers, including those in the supply and distribution networks, would have lost their jobs. Marchionne’s (1) recent deal with Chrysler and the attempt to enter into the orbit of Opel, with a debt burden of €10 billion on its shoulders, is none other than the attempt to surmount the crisis by the process of concentration; a function also of the expectation that the already highly competitive global vehicle market will eventually be “blocked” by the arrival, in a big way, of China and India. All of this does not signify the inglorious end of neo-liberalism, but the bankruptcy of capitalism, of its mode of producing and distributing wealth, of the perverse exacerbation of its insoluble contradictions.

This is the setting of all the policies to squeeze the most out of the workforce.

Capital, with the “responsible” collaboration of the unions, seeks first of all to delay new wage agreements for as long as possible. At times it is not only a question of months, but of years, before the parties manage to reach an agreement. When they do, capital tries to impose yet more sacrifices centred round deferring wage rises; or else a wage rise is conceded - but on the assumption that any increase will be within, or rather well reduced, by inflation and far below any increase in productivity.

The other route capital takes to recover profit margins is that of lengthening the working day. Even though it carries on increasing relative surplus value, by increasing the productivity of labour through technological innovation, this only increases the mass of profit whilst, however, lowering the rate. Capital is thus also obliged to return to the pursuit of absolute surplus value, obtained by prolonging the working day. It is like an historical paradox, as if capitalism had gone back two centuries, except that it is the reality of modern capitalism which is imposing this situation.

At the present stage it is no longer enough to respond to the falling rate of profit by increasing the mass of capital. Capital also must attempt to add absolute surplus value to the relative surplus value, in a sort of ceaseless effort which never succeeds in overcoming the insoluble contradictions that the process of valorisation continually poses to its being. Now that it has at its disposal an increasingly feeble proletariat, divided politically as much as it is economically, with no job security and easily blackmailed, almost everywhere capital is beginning to impose a longer working day without any increase in wages. We are just at the beginning, but these kind of practices, even if they are unofficial or presented as makeshift responses to specific crisis situations, have already come into operation. The French experiment with the 35 hour week, which in any case is only nominal since it is hardly ever put into practice, was obtained at the expense of job security and the relinquishing of all opposition to its implementation. In the same vein, the German metalworkers’ union (IGMetall) has agreed that in certain instances the working day can be prolonged for 10- 12 hours in exchange for curtailment of layoffs. In Japan this has been the practice for about three decades even though it has never been made official either by the unions or the bosses. A worker in a Japanese factory, above all in those facing international competition, can work up to 10 or 12 hours a day, with only two Sundays off per month, for no extra pay or else for a derisory, almost zero amount. Amongst information technology workers in the USA today 31% work for more than 50 hours a week with an increase in production of 70%. In 1980 only 21% worked more than 50 hours. The same thing is happening in retail and trade, in catering, in metalworking and in manufacturing in general. All these situations are just the beginning. In future we can only expect capital to reinforce its attacks on labour power.

One example of what is in store has been provided by the Australian prime minister. He proposes making strikes illegal throughout the economy, including services, and to make it legally possible to lay off anyone, whatever the moment and for whatever reason. In Italy the “Sacconi law” (2) proposed by the government, besides providing for the possibility of prolonging the working week (42-45 hours, depending on circumstances), has concocted a way of neutralising strikes, in practice of banning them, in order to safeguard the interests of society as a whole, and ends up formulating the virtual strike - one where the workers can announce they are on strike without, however, abstaining from work although they would relinquish their payment for the day as if they really had not been at work. Paradoxical? Certainly. But there is no limit to the fantasies of capital in crisis.

The falling rate of profit even imposes the need to contain the depreciation of constant capital. Here the most significant aspect concerns the relation between constant capital and its material volume, even though the rate of exploitation remains the same. In normal conditions the increase in constant capital is faster than the increase in variable, determining the fall in the rate of profit. However if, thanks to a higher productivity of labour, the value of constant capital, even though it expands, grows proportionally less than overall mass of means of production put into operation by the same quantity of labour power, the fall in the rate can be slowed down and, in some cases and for a limited period, annulled. This is what has happened in the extraordinary case of the microprocessor “revolution”, where a higher rate of increase in productivity has been achieved because the increase in constant capital was proportionally lower than the mass of means of production operating in the productive system. Moreover, the opportunity created by this technological revolution to diversify production at the same time as using the same constant capital, makes for its depreciation which in turn affects the rate of profit. An example arose in the automobile field a few years ago with the collaboration between Fiat and Ford. The two groups agreed to produce the Ka and the Panda in Poland.

A single building, wages well below the domestic level and, thanks to diversified production, the same machinery was able to produce the chassis of both cars, saving at least 40% on the assembly costs.

Still on the subject of depreciation of constant capital, there is the attempt to reorganise stocks of raw materials and partly worked up goods. After forcing the withdrawal of job security on variable capital, on the basis of “use the labour then throw it away”, or rather by utilising labour power only at the key moments of production, a similar system has been brought in to reduce the costs of a part of constant capital. The introduction of just in time, that is the ordering of parts and raw materials only just at the moment they will be used in production, has transformed storage and maintenance costs as well as reducing the risk of stock deteriorating. Such innovations are certainly rational and work to reduce the costs of production, but they are the offspring of a compelling necessity: the need to contain the damage done by falling profits, in this case by a depreciating quota of constant capital - the circulating part. This kind of reorganisation of one of the factors of production is on a par with the moves to increase labour flexibility with its resulting job insecurity. For capital, raw materials and labour power are simply commodities that have to be employed in the production process at the minimum possible cost and - in order to remain competitive and keep up profitability - only at the times when they are instrumental in valorisation.

Reducing the cost of raw materials can also help to lower the value of constant capital. In the present epoch, where the domination of finance capital has reached its apex, the power relationship between the imperialist centres and the so-called periphery allows the first to impose absolutely unequal conditions on the second when it comes to the supply and payment for raw materials.

An example of this is the politics of debt. Far from waving the flag of neoliberalism, of free competition in a free market, the stronger and more aggressive the imperialists are the more they succeed in achieving their objective of inflicting commercial blackmail on the debtor countries. Primarily the blackmail consists of renegotiating the terms of trade with these countries which are rich in raw materials but up to their necks in debt. They can either obtain new terms for the debt or prolong the repayment period, so long as they submit to a new series of conditions.

First amongst them is the demand to clean up the public finances, an inevitable precursor to the privatisation of national assets. Privatisation allows the big international companies to take over or get a stake in key industries so that they have absolute control over the extraction and distribution of strategic raw materials without any government interference.

In the second place, the terms of the credit agreements usually give the creditors priority over supply with a corresponding reduction in purchase price. In other cases, when imperialism gains a monopoly over demand the effect is the same. When the pressure of blackmail is not enough it is outright force which determines access to the market and the price levels of raw materials. It is no accident that American imperialism, with its voracious network of national and international companies, with or without the support of the IMF and the UN, has brought the raw materials markets of Central and South America down to their lowest level. The US has unleashed a continuous series of wars for oil and there is nothing to suggest that this will not continue, in direct proportion to the sharpening of the national and international crisis, even if the Obama administration presents itself as different from the previous one, without, however, rejecting its “imperial” objectives.

We can sum this all up easily by concluding that imperialist aggression towards international markets is directly proportional to the damage caused by the falling rate of profit. The lower the profits, the greater the necessity to resort, by means of blackmail or force, to a series of counter-measures which allow capitalism a higher organic composition and enable it to continue surviving its own contradictions. Thus the price is paid by the periphery and capitalism’s weakest competitors and, above all, by the respective national and international proletariat.

There are countless examples for anyone, even the most unobservant, to note. There isn’t a strategically important area without an armed US presence, whether it be the Gulf, the Middle East, central Asia. Moreover, even if at the moment it is at a lower level, Europe, Russia and China also play a bellicose role. Wars over oil and for the control of raw materials have been going on for years without any solution.

The present crisis cannot do anything else but exacerbate the contradictions at the heart of the capitalist social and productive system. As it is, social production is falling. GDP figures for the USA, Europe and Japan are well below zero. Entire sectors of production are on the brink of collapse. The credit system is writhing. The underclass is prevented from consuming. The international proletariat is subjected to attacks by capital on every possible front - work, higher exploitation, growing pauperisation - while speculation and parasitism continue to grow in parallel, despite all the appeals to financial morality, as if this devastating crisis of capitalism was reducible to the absence of regulations and the need for “ethical” behaviour. This crisis demonstrates how far capitalism is decadent and how its gigantic contradictions are generated from within the system of production itself and its internal mechanisms for the valorisation of capital, and which, as a result of the falling rate of profit, are making the social and political system it has generated even more aggressive, not to say, ferocious.

Delocalisation of Production and Export of Financial Capital

As always, low profit rates have imposed a relative overproduction of capital on the system of production. In turn, the overproduction of capital presupposes an excess of commodities. This absolutely does not mean that too many goods have been produced and that there is an excess of productive capacity in relation to social needs, or even that too much wealth has been produced in the form of capital. All it means is that, within the narrow and contradictory relations of capitalist production, low profit rates lead to a growing mass of capital which cannot be invested productively. This increases the stock of unsold commodities as a result of the low level of demand which cannot absorb them at the existing price and the suppliers of raw materials, the factories, reduce production or else are forced to close down altogether.

It follows that one way out of the crisis generated by the falling rate of profit, besides speculation, is to move production abroad where the cost of raw materials, of infrastructure and, above all, labour power, are distinctly less. In the present epoch the export of capital with its accompanying delocalisation of production has developed in geometric sequence. From the serious crisis of the Seventies until today all the highly industrialised countries have been throwing everything at finding economic zones where the cost of labour power is as low as possible, where trade union protection is minimal or nonexistent.

The more delocalisation succeeds in finding these conditions, the more efficacious is the antidote to the falling rate of profit.

Every advanced capitalist state, depending on its imperialist weight, seeks out its own zone, its own sphere of influence, in the search for an impoverished proletariat that is obliged to accept whatever wage is offered by the foreign companies. This is one aspect of globalisation. For a capital which is suffocating from lack of profits, the tearing down of customs barriers, the free circulation of capital and commodities, the possibility of decentralising production to wherever it likes and to have at its disposal, without any union constraints, an international proletariat whose cost is at least 10- 15 times lower than at home, this is manna which no-one can turn down.

Apart from imperialist giants, like the USA which has colonised the south of the American continent and parts of Asia, including China, or Japan which has taken the rest of Asia and China (40% of Chinese exports are labelled “made in the USA” or “made in Japan”), old Europe is no less involved. France continues to exploit its ex-colonies of the Maghreb and central-west Africa. Germany has positioned itself in the ex-soviet republics and little old Italy has managed to decentralise production beyond the Adriatic, to Romania, Bulgaria and Poland but also to Brazil and Argentina.

As usual, this is not new. For more than a century decentralisation of production has taken place in the four corners of the world. However, from the 2nd World War until today, and with particular intensity over the last twenty years, the necessity to re-establish tolerable profit margins has made the race for low cost labour markets a question of life and death for economies with a high organic composition of capital.

Those who deny that the tendency for the rate of profit to fall is a problem for modern capitalism, who argue that all these manifestations of countertendencies are absolutely nothing new and that, on the contrary, we are witnessing a new phase of economic expansion as exemplified by China, should remember that the Asian economic miracle is partly the result of this capitalist contradiction. China’s extraordinary economic development, which has allowed Beijing to talk of an average rate of growth of 10% over the last fifteen years, is based on three factors. The relentless decentralising of production, accompanied by new technology, on the part of countries in crisis as a result of the low rate of profit, such as the USA, Japan, South Korea and, in part, western Europe. The arrival of enormous amounts of finance capital from the same countries, for the simple reason that in China they had, and still have, at their disposal a proletariat with extremely low wages, up to 80-90% lower; a working day which can go up to 14 hours long; and no union cover, either for health and safety or for job security.

It is self-evident that in the long term development at this rate in China will come to a halt, as it did previously for the NIC (newly industrialised countries) in the Sixties and Seventies, not because capitalist progress has reached its apex, but because Chinese capitalism will be forced to suffer the same consequences as the highly industrialised countries are today experiencing. Growth in these countries cannot be equated with capitalism in its phase of expansion when there were new areas of development and economic growth to open up.

On the contrary, these “countertendency” experiences fall entirely within the decadent phase which afflicts international capital as a result of the tendency for the rate of profit to fall.

How to get out of this? Only by the revival of the class struggle under the guidance of the revolutionary party, which does not limit itself to economic demands, whether defensive or otherwise, even if these are the point of departure. Rather, the party will also begin to challenge the mechanisms that capital uses to safeguard its economic and political interests. To move against capital means first of all challenging the conditions of existence for capitalist relations of production: productive relations which are responsible for increasingly intense exploitation, for millions of workers suffering mortifying unemployment, for the devastating economic crisis which accompanies its mode of creating wealth, which leads to warfare as a means of continuing the process of accumulation and extortion of surplus value which is at the basis of its existence. Otherwise the working class will vacillate as it tries to reconcile itself with the irreconcilable, with capital, which is opposed to the present and future interests of the proletariat.

Fabio Damen(1) Sergio Marchionne, Chief Executive of Fiat.

(2) Maurizio Sacconi, Minister of Labour, Health and Social Policy. The draft bill presented to parliament on 29.2.09, amongst other things, aims to prevent strikes in “essential services” and includes the requirement for public transport workers to abandon the right to strike in favour of the “virtual strike”.

Academic economists and legal experts in Italy have been toying with the concept of the “virtual strike” for a decade or so. In the academic discussion the employers are supposed to sacrifice the income they would have lost if a real withdrawal of labour had gone ahead (by making a donation to charity, for example). Needless to say, the real-life, Sacconi version of the virtual, does not involve any loss for the employers.

Revolutionary Perspectives

Journal of the Communist Workers’ Organisation -- Why not subscribe to get the articles whilst they are still current and help the struggle for a society free from exploitation, war and misery? Joint subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (our agitational bulletin - 4 issues) are £15 in the UK, €24 in Europe and $30 in the rest of the World.

Revolutionary Perspectives #52

Start here...

- Navigating the Basics

- Platform

- For Communism

- Introduction to Our History

- CWO Social Media

- IWG Social Media

- Klasbatalo Social Media

- Italian Communist Left

- Russian Communist Left

The Internationalist Communist Tendency consists of (unsurprisingly!) not-for-profit organisations. We have no so-called “professional revolutionaries”, nor paid officials. Our sole funding comes from the subscriptions and donations of members and supporters. Anyone wishing to donate can now do so safely using the Paypal buttons below.

ICT publications are not copyrighted and we only ask that those who reproduce them acknowledge the original source (author and website leftcom.org). Purchasing any of the publications listed (see catalogue) can be done in two ways:

- By emailing us at uk@leftcom.org, us@leftcom.org or ca@leftcom.org and asking for our banking details

- By donating the cost of the publications required via Paypal using the “Donate” buttons

The CWO also offers subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (at least 4 issues):

- UK £15 (€18)

- Europe £20 (€24)

- World £25 (€30, $30)

Take out a supporter’s sub by adding £10 (€12) to each sum. This will give you priority mailings of Aurora and other free pamphlets as they are produced.

ICT sections

Basics

- Bourgeois revolution

- Competition and monopoly

- Core and peripheral countries

- Crisis

- Decadence

- Democracy and dictatorship

- Exploitation and accumulation

- Factory and territory groups

- Financialization

- Globalization

- Historical materialism

- Imperialism

- Our Intervention

- Party and class

- Proletarian revolution

- Seigniorage

- Social classes

- Socialism and communism

- State

- State capitalism

- War economics

Facts

- Activities

- Arms

- Automotive industry

- Books, art and culture

- Commerce

- Communications

- Conflicts

- Contracts and wages

- Corporate trends

- Criminal activities

- Disasters

- Discriminations

- Discussions

- Drugs and dependencies

- Economic policies

- Education and youth

- Elections and polls

- Energy, oil and fuels

- Environment and resources

- Financial market

- Food

- Health and social assistance

- Housing

- Information and media

- International relations

- Law

- Migrations

- Pensions and benefits

- Philosophy and religion

- Repression and control

- Science and technics

- Social unrest

- Terrorist outrages

- Transports

- Unemployment and precarity

- Workers' conditions and struggles

History

- 01. Prehistory

- 02. Ancient History

- 03. Middle Ages

- 04. Modern History

- 1800: Industrial Revolution

- 1900s

- 1910s

- 1911-12: Turko-Italian War for Libya

- 1912: Intransigent Revolutionary Fraction of the PSI

- 1912: Republic of China

- 1913: Fordism (assembly line)

- 1914-18: World War I

- 1917: Russian Revolution

- 1918: Abstentionist Communist Fraction of the PSI

- 1918: German Revolution

- 1919-20: Biennio Rosso in Italy

- 1919-43: Third International

- 1919: Hungarian Revolution

- 1930s

- 1931: Japan occupies Manchuria

- 1933-43: New Deal

- 1933-45: Nazism

- 1934: Long March of Chinese communists

- 1934: Miners' uprising in Asturias

- 1934: Workers' uprising in "Red Vienna"

- 1935-36: Italian Army Invades Ethiopia

- 1936-38: Great Purge

- 1936-39: Spanish Civil War

- 1937: International Bureau of Fractions of the Communist Left

- 1938: Fourth International

- 1940s

- 1960s

- 1980s

- 1979-89: Soviet war in Afghanistan

- 1980-88: Iran-Iraq War

- 1980: Strikes in Poland

- 1982: First Lebanon War

- 1982: Sabra and Chatila

- 1986: Chernobyl disaster

- 1987-93: First Intifada

- 1989: Fall of the Berlin Wall

- 1979-90: Thatcher Government

- 1982: Falklands War

- 1983: Foundation of IBRP

- 1984-85: UK Miners' Strike

- 1987: Perestroika

- 1989: Tiananmen Square Protests

- 1990s

- 1991: Breakup of Yugoslavia

- 1991: Dissolution of Soviet Union

- 1991: First Gulf War

- 1992-95: UN intervention in Somalia

- 1994-96: First Chechen War

- 1994: Genocide in Rwanda

- 1999-2000: Second Chechen War

- 1999: Introduction of euro

- 1999: Kosovo War

- 1999: WTO conference in Seattle

- 1995: NATO Bombing in Bosnia

- 2000s

- 2000: Second intifada

- 2001: September 11 attacks

- 2001: Piqueteros Movement in Argentina

- 2001: War in Afghanistan

- 2001: G8 Summit in Genoa

- 2003: Second Gulf War

- 2004: Asian Tsunami

- 2004: Madrid train bombings

- 2005: Banlieue riots in France

- 2005: Hurricane Katrina

- 2005: London bombings

- 2006: Anti-CPE movement in France

- 2006: Comuna de Oaxaca

- 2006: Second Lebanon War

- 2007: Subprime Crisis

- 2008: Onda movement in Italy

- 2008: War in Georgia

- 2008: Riots in Greece

- 2008: Pomigliano Struggle

- 2008: Global Crisis

- 2008: Automotive Crisis

- 2009: Post-election crisis in Iran

- 2009: Israel-Gaza conflict

- 2020s

- 1920s

- 1921-28: New Economic Policy

- 1921: Communist Party of Italy

- 1921: Kronstadt Rebellion

- 1922-45: Fascism

- 1922-52: Stalin is General Secretary of PCUS

- 1925-27: Canton and Shanghai revolt

- 1925: Comitato d'Intesa

- 1926: General strike in Britain

- 1926: Lyons Congress of PCd’I

- 1927: Vienna revolt

- 1928: First five-year plan

- 1928: Left Fraction of the PCd'I

- 1929: Great Depression

- 1950s

- 1970s

- 1969-80: Anni di piombo in Italy

- 1971: End of the Bretton Woods System

- 1971: Microprocessor

- 1973: Pinochet's military junta in Chile

- 1975: Toyotism (just-in-time)

- 1977-81: International Conferences Convoked by PCInt

- 1977: '77 movement

- 1978: Economic Reforms in China

- 1978: Islamic Revolution in Iran

- 1978: South Lebanon conflict

- 2010s

- 2010: Greek debt crisis

- 2011: War in Libya

- 2011: Indignados and Occupy movements

- 2011: Sovereign debt crisis

- 2011: Tsunami and Nuclear Disaster in Japan

- 2011: Uprising in Maghreb

- 2014: Euromaidan

- 2016: Brexit Referendum

- 2017: Catalan Referendum

- 2019: Maquiladoras Struggle

- 2010: Student Protests in UK and Italy

- 2011: War in Syria

- 2013: Black Lives Matter Movement

- 2014: Military Intervention Against ISIS

- 2015: Refugee Crisis

- 2018: Haft Tappeh Struggle

- 2018: Climate Movement

People

- Amadeo Bordiga

- Anton Pannekoek

- Antonio Gramsci

- Arrigo Cervetto

- Bruno Fortichiari

- Bruno Maffi

- Celso Beltrami

- Davide Casartelli

- Errico Malatesta

- Fabio Damen

- Fausto Atti

- Franco Migliaccio

- Franz Mehring

- Friedrich Engels

- Giorgio Paolucci

- Guido Torricelli

- Heinz Langerhans

- Helmut Wagner

- Henryk Grossmann

- Karl Korsch

- Karl Liebknecht

- Karl Marx

- Leon Trotsky

- Lorenzo Procopio

- Mario Acquaviva

- Mauro jr. Stefanini

- Michail Bakunin

- Onorato Damen

- Ottorino Perrone (Vercesi)

- Paul Mattick

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Vladimir Lenin

Politics

- Anarchism

- Anti-Americanism

- Anti-Globalization Movement

- Antifascism and United Front

- Antiracism

- Armed Struggle

- Autonomism and Workerism

- Base Unionism

- Bordigism

- Communist Left Inspired

- Cooperativism and autogestion

- DeLeonism

- Environmentalism

- Fascism

- Feminism

- German-Dutch Communist Left

- Gramscism

- ICC and French Communist Left

- Islamism

- Italian Communist Left

- Leninism

- Liberism

- Luxemburgism

- Maoism

- Marxism

- National Liberation Movements

- Nationalism

- No War But The Class War

- PCInt-ICT

- Pacifism

- Parliamentary Center-Right

- Parliamentary Left and Reformism

- Peasant movement

- Revolutionary Unionism

- Russian Communist Left

- Situationism

- Stalinism

- Statism and Keynesism

- Student Movement

- Titoism

- Trotskyism

- Unionism

Regions

User login

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.